Homework 2#

Note

You are free to discuss these questions with your classmates and on our class slack, but you must write your own solutions, including your own source code.

All code should be uploaded to github classroom under the Assigment Homework (all weeks) along with any analytic derivations, notes, etc.

Solving ODEs: simple pendulum#

Consider a simple pendulum. The equations of motion are:

\[\dot{\theta} = \omega\]\[\dot{\omega} = -\frac{g}{L} \sin \theta\]where \(\theta\) is the angular displacement from vertical and \(\omega\) is the angular velocity. The angular acceleration in this case is \(\alpha = -(g/L) \sin\theta\). In your intro mechanics class, you probably solved this using the small-angle approximation an found the solution has the form:

\[\theta(t) = A \cos(\tfrac{2\pi}{T} t + \phi)\]where the period (in the small-angle approximation) is:

\[T = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{L}{g}}\]We will solve this system without making the small-angle approximation. For larger amplitude displacements, the period takes the form:

\[T = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{L}{g}} \left ( 1 + \frac{1}{16}\theta_0^2 + \ldots \right )\](see, e.g, Wikipedia), where \(\theta_0\) is the initial angular displacement of the pendulum.

The total energy of the system is

\[E = \frac{1}{2} m L^2 \omega^2 - mg L \cos \theta\]Solve the pendulum system using both the Euler and Euler-Cromer methods. Pick \(L = 10\) m and \(g = 10\) \(\text{m/s}^2\). Compare the solutions for \(\theta = 10^\circ\) and \(100^\circ\). Make a plot of both \(\theta(t)\) vs. \(t\) and \(E\) vs. \(t\). Notice the stark difference in the behavior between the two methods.

In each case, estimate the period from your numerical solution.

Now consider the velocity Verlet method (kick-drift-kick) we discussed in class. As we saw in class, this applies when the acceleration term (\(\alpha\) in our case) does not depend on the velocity (\(\omega\) for us).

Implement this method for the simple pendulum and estimate its convergence by comparing the total energy after several periods to the initial energy for a variety of choices of \(\tau\).

Use a fixed timestep for all of these integrations.

Solving ODEs: a stable three-body system#

The equation of motion for a body in a gravitational three-body system is given by

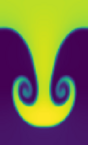

The three-body problem famously has no analytical solution, and these systems are characterized as being highly chaotic and inherently unstable. However, stable three-body orbits have been found numerically. These are unlikely to be found in nature due being highly sensitive to initial conditions and perturbations. One of these stable orbits is the so-called figure-eight orbit, which is what we will be simulating here. For this exercise, we will set \(G=1\).

Write an adaptive 4th order Runge-Kutta (RK4) method to integrate a set of equations.

Use your adaptive RK4 method to integrate the above equation of motion for each of the three bodies in a gravitational system. Use the following initial conditions and evolve for a total time \(T = 6.5\).

\(\bf{x}_1(t=0) = -\bf{x}_3(t=0) = (-0.97000436, 0.24308753)\)

\(\bf{x}_2(t=0) = (0.0, 0.0)\)

\(\bf{v}_1(t=0) = \bf{v}_3(t=0) = (0.4662036850, 0.4323657300)\)

\(\bf{v}_2(t=0) = (-0.93240737, -0.86473146)\)

Make a plot of the positions of each of the bodies as a function of time. Does it look as you expected?

Make a plot of the total energy of the system.

Try playing around with the tolerances, the initial conditions, and the total simulation time. What do you observe?

Bonus exercise:#

Thousands of stable 3-body orbits have been found numerically. Look through this paper, choose some initial conditions for other stable configurations, and solve them using your integrator.